Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it’s investigating the financials of Elon Musk’s pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, ‘The A Word’, which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.

Read more

Donald Trump’s administration is jailing 178 Venezuelan immigrants at a high-security U.S. military prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, but nearly one-third of detainees are considered “lower-threat” and likely do not have any serious criminal records, according to court filings.

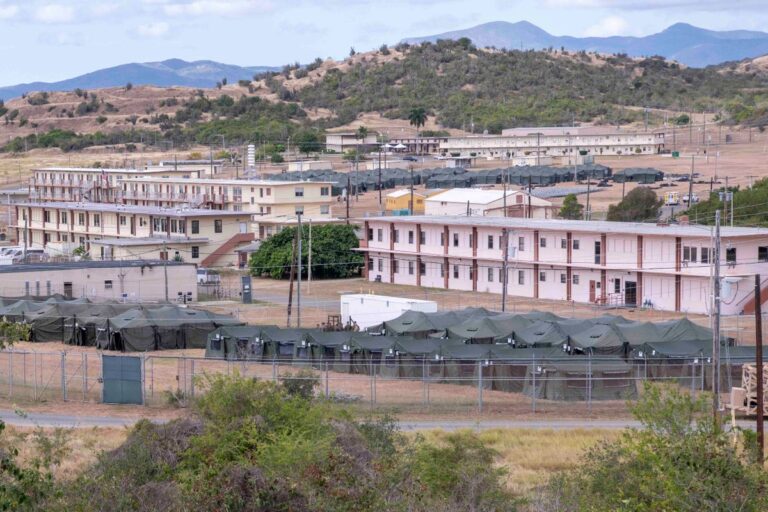

At least 128 people who are considered “higher-threat” immigrants are detained inside Camp IV, which resembles facilities used to house prisoners of war, according to sworn statements from Homeland Security and U.S. Army personnel.

Camp IV has a capacity of approximately 175 people, but its current capacity is 131 due to “ongoing maintenance being performed in certain cells,” according to the statements.

The remaining 51 “lower-threat” detainees — roughly 28 percent — are being held “in and around” a barracks-like “Migrant Operations Center,” the filings say.

The statements were attached to the Department of Justice’s response to a lawsuit from immigration attorneys, civil rights groups and the families of detained immigrants demanding access to the prison to offer legal aid.

A lawsuit from the ACLU and Center for Constitutional Rights, among others, argues that detainees have “effectively disappeared into a black box and cannot contact or communicate with their family or attorneys.”

open image in gallery

The government has offered “no legal authority” for this “unprecedented action” while cutting off “any means of communication” for detainees to the outside world, plaintiffs wrote in a lawsuit filed in Washington, D.C. last week.

In response to the lawsuit, Justice Department lawyers claim that the facility does offer them access to legal counsel, but that plaintiffs are relying on an “overstated framing of the limited rights of immigration detainees,” all of whom are Venezuelan nationals subject to final removal orders from the United States.

“Detainees have not been deprived of a constitutional right to access counsel” because they “do not have the same due process protections,” according to the Justice Department.

The detainees there “do not have a statutory right to counsel,” they argued.

Instructions in English and Spanish telling detainees how to make phone calls to counsel are posted at the facility, and “retained counsel for the detainees are also able to make requests for phone calls to their clients,” according to Justice Department lawyers.

Detainees also “have the ability to send and receive legal mail through the process used by law-of-war detainees,” though the administration admits that the facility is “not presently offering the opportunity for in-person visits to immigration detainees,” the filing states.

open image in gallery

Trump and Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem have repeatedly defended use of the facility — which opened in 2002 to hold terrorism suspects during the War on Terror — to jail suspected Tren de Aragua gang members and “the worst of the worst and illegal criminals,” according to Noem.

But “lower-threat” immigrants may include nonviolent immigrants who are in the U.S. illegally but who have never been charged or convicted of violent offenses or other serious crimes, according to federal guidelines.

Use of the facility, where Trump has suggested detaining as many as 30,000 people, has drawn international scrutiny from humanitarian groups fearing potential for abuse in the secrecy of an offshore facility beyond the nation’s borders.

Over the past month, U.S. military personnel have been seen erecting tents around the facility,

“Guantanamo is a breeding ground for violence, abuse, and neglect,” according to Jennifer Babaie, director of advocacy and legal services with Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center in El Paso, Texas, New Mexico and Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua, which is the lead plaintiff in the case.

“Many of these men have already been subjected to countless human rights abuses and due process violations,” she said in a statement last week. “Keeping them in Guantanamo without regular access to lawyers and loved ones while at the same time spreading unfounded accusations against them all on the basis of what they look like and where they come from, is dangerous, violent, and completely unacceptable.”

Earlier this month, a judge blocked the administration from transferring three Venezuelan men to Guantanamo after they were held in Immigration and Customs Enforcement custody for more than a year.

The men had passed credible fear interviews as part of their request for asylum in the United States, where they were seeking refuge after fleeing their home country.

In response to the judge’s order, the administration deported them to Venezuela.

Trump-appointed District Judge Carl Nichols is overseeing the latest Guantanamo case. A hearing has not yet been scheduled.