A former federal worker had been working as a designer at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) for five years when a 5:30 a.m. email put the kibosh on her government career.

She had been enjoying her work. “It meant something to help protect the public,” she said. But the email, sent April 1, told her that she was terminated and directed her not to come into the office. “That was it,” said the worker, who spoke with Newsweek on the condition of anonymity. “No meeting, no warning. Our entire branch was just suddenly gone.”

Forced to seek alternative employment, and despite previous experience in the private sector, including at a large international bank, the former federal employee is struggling. She has sent more than 150 applications to large companies, but said she has only had one interview. She is among a group of federal workers, having recently been laid off, that is finding it challenging to join the private sector.

“I’m scared for my future,” she said. “Scared about how I’m going to pay rent. Scared about not having health insurance. I am full of rage at this administration. I have never witnessed such cruelty. Not just toward people like me, but toward innocent people here and abroad. People will die because of what’s happening.”

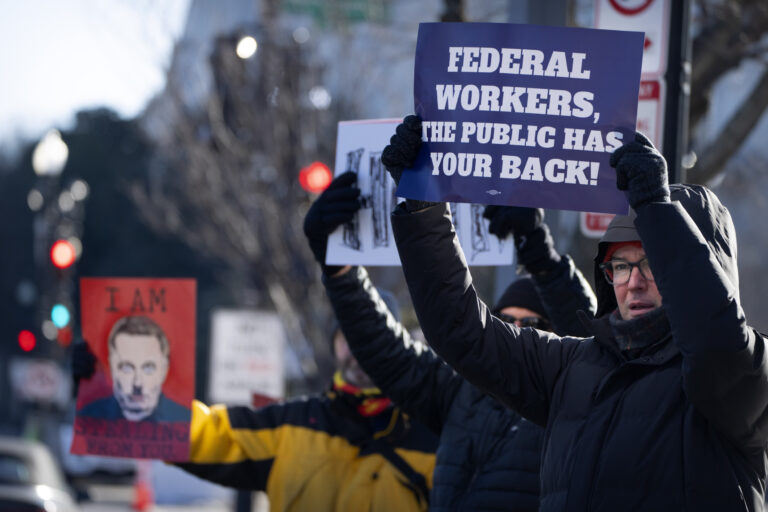

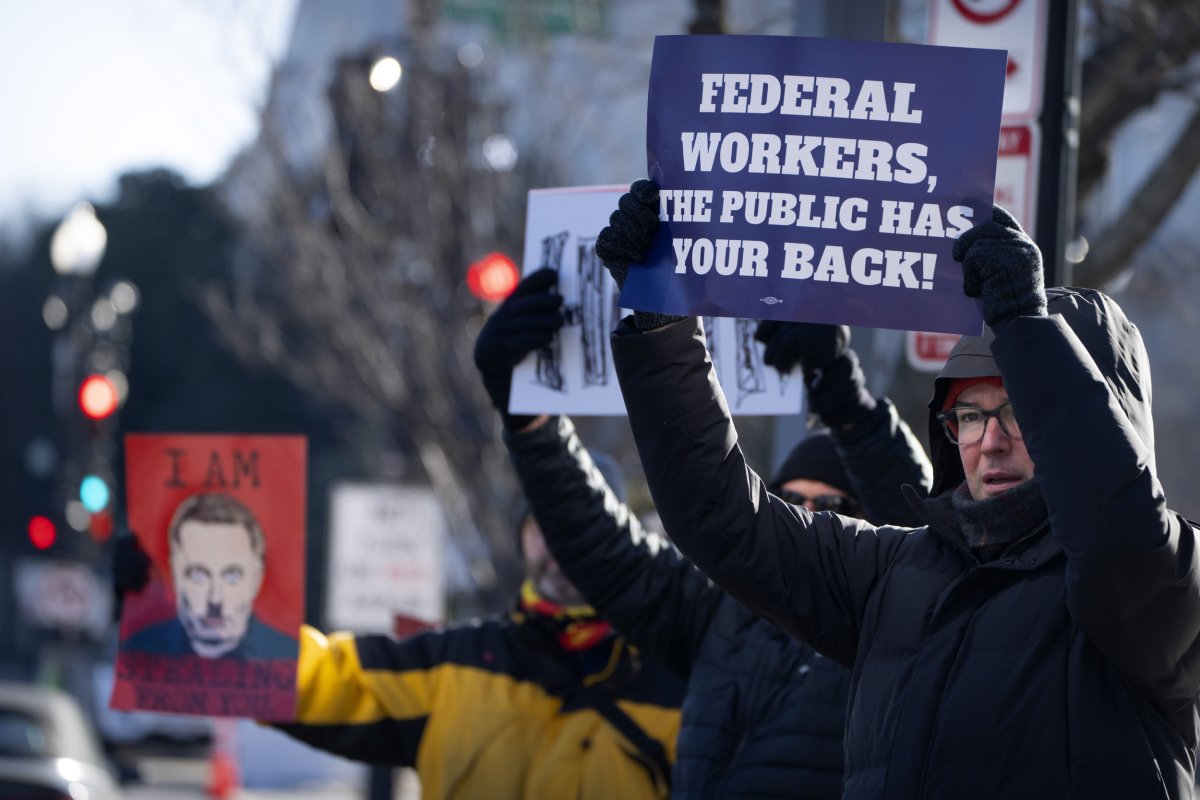

AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein

Since assuming office for the second time, President Donald Trump’s administration has prioritized cutting waste and streamlining services in the federal government. To that end—and along with the newly created Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE)—the administration has implemented hiring freezes and mass layoffs.

Federal Workers Suffering From Bad Rep

There are 2.4 million federal workers in the U.S., according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). While there is no official data revealing how many people have been fired, The New York Times estimates the figure at 135,000. The layoffs and accusations of government inefficiency have, in some federal worker’s eyes, led to a culture where the federal workforce is undervalued.

“It feels like there’s a perception that if you worked in the federal government, you must be slow or not used to real deadlines,” the former CDC employee said. “A recruiter literally told me, ‘This job is pretty fast-paced, so we’re looking for someone from a more agile environment.’ Another said I might not be a good ‘cultural fit,’ which felt like code.”

Chris Barnes joined the Food and Drug Administration in 2012 and planned to stay there for the rest of his career. But on April 1, he was put on administrative leave from what he said, “was the best job in the world.”

Since then “the job search has been a disaster,” he said. “I’ve applied to so many places that I have no idea where I have open applications.”

Another federal worker who is employed at the Social Security Administration has given up looking for a new job because of the challenges of moving to the private sector.

“In my search I’ve found routinely that if I were to move out of the federal workforce and to the private sector, I’d take a $40,000 per year hit, on average,” they said, speaking to Newsweek anonymously.

“My skills are very specific to work at my job as a federal worker. They do not translate easily to the private sector. I’ve given up looking. It’s emotionally draining, to see over and over again how desolate things are with jobs available in general, and my specialty in particular.”

“There may be several factors involved” in making it difficult for federal workers to get new jobs, according to David H. Rosenbloom, a public administration professor at the School of Public Affairs at American University in Washington, D.C.

One is “the widespread image of the federal workforce as of limited competence,” he told Newsweek. Another is potential “age discrimination,” as the federal workforce leans older than the general workforce.

He added that federal employees’ specializations and expertise can be “an imperfect match with the needs of private employers” and that there are “legal and ethical constraints limiting how feds can use their specializations after leaving the federal government.”

A Shrinking Job Market

Indeed, there are broader issues with the U.S. job market of which former feds are just one component. While the unemployment rate in the U.S. is fairly low at 4.2 percent, according to BLS, there has been a fall in job vacancies in recent months, suggesting employers are hiring less and the rate of unemployment is higher for young graduates.

Susan Houseman, a senior economist at the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, said that wider economic factors were contributing to federal workers’ plight.

“The difficulty is related to the fact that federal workers are concentrated in certain areas, and the large-scale reductions in force, along with cuts to federal grants and contracts, are impacting regional economies,” she told Newsweek.

“In the D.C. area, for example, those who lose their government jobs normally would look for employment in the private sector, but the private sector too has been negatively impacted by cuts in grants and contracts, depressing overall demand for workers.”

While laid-off federal workers continue to look for jobs, some Americans are hoping to join the federal government after the hiring freeze expires in July. To do so, they will have to answer a series of essays as part of the job recruitment process, including one about how they would “help advance” Trump’s policy priorities.

In the meantime, former federal workers will continue to wrangle with a competitive job market. The CDC worker said that, before joining the agency, she was getting regular interviews for jobs in the private sector. “The only difference now is that I’m a former fed,” she said. “And with ‘CDC’ on my resume, it feels like I can’t even get in the door to show what I can do.”